|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

Spies, allies, and enterprise: the strange story of ULA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyxLAezc9k0

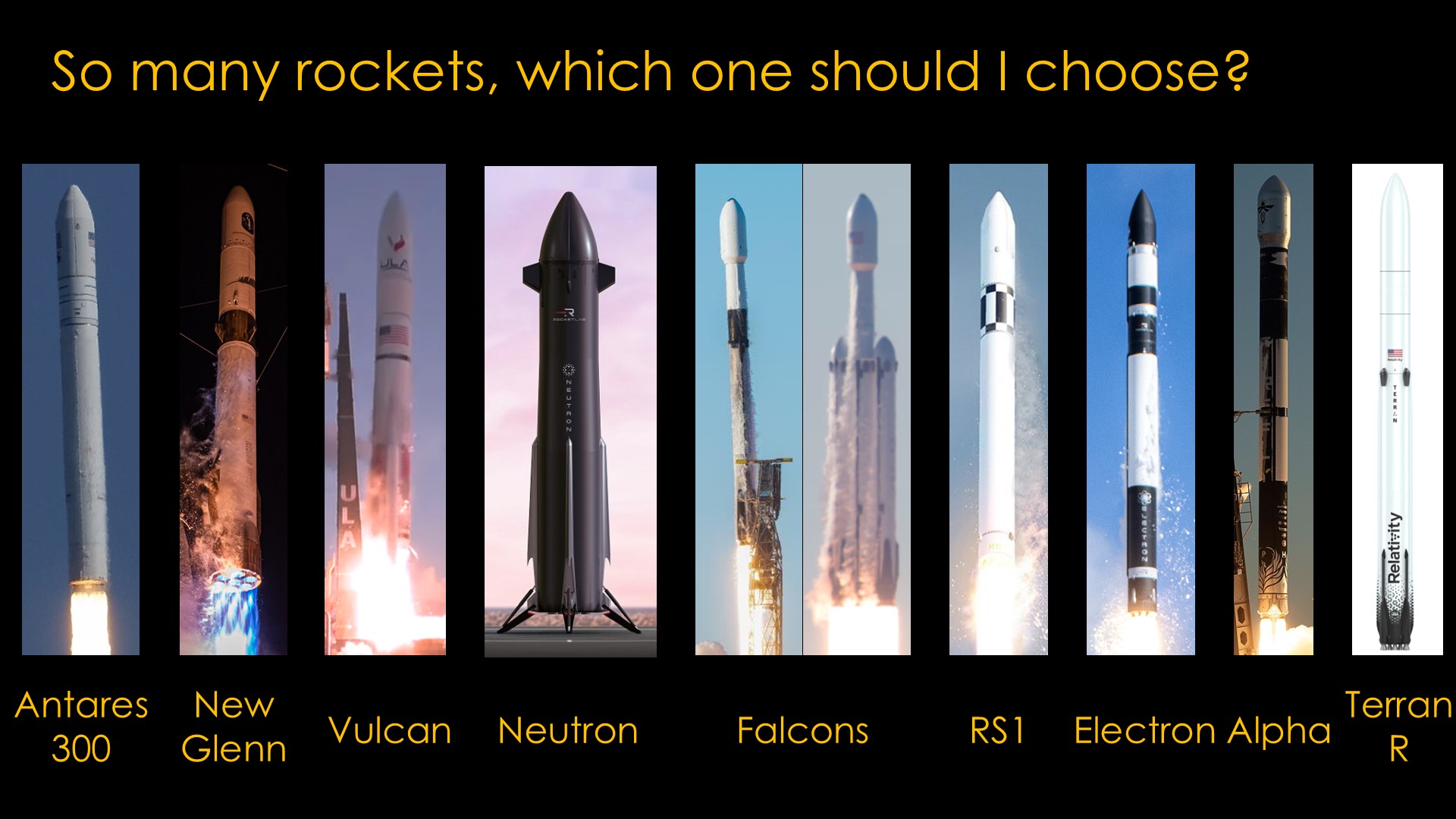

There are so many rockets out there - some flying and some in development.

Which ones are going to be successful?

There seems to be a lot of unbridled optimism in the launch vehicle world...

It's a foolproof plan...

(read)

But maybe, just maybe, it's not quite that simple...

Rockets do not exist in a vacuum... Well, actually existing in a vacuum is one of their primary jobs, but rockets become successful by launching payloads, and those payloads fit into separate markets.

To be successful, you need to build a rocket that customers will pay you to use, and that means that you need to be successful in a specific market. This video will be focused on the different markets; the next video will focus on the rockets.

Let's look at a simple example of a market.

We can talk about vehicles, but there are an endless number of vehicle types and a train engine and a formula 1 race car are not interesting to the same customer. I would therefore not consider "vehicles" to be an interesting market.

If we limit our market to cars, there are some customers who might look at different types - marketing and economics people call this "substitutability" - but a customer of one type would not look at most of the other types. Still not an interesting market.

If we further refine the group of cars down to what Car and Driver called "roadsters that cost less than $50,000", then we have defined a market where a customer might choose any of these cars. That's easy to analyze.

But it is perhaps too small of a definition. Customers looking at these cars are probably looking at similar cars that have hard tops and also looking at 4 door versions.

When looking at launch systems, we need to understand what sort of customers they are looking at serving and how the existing companies are serving that market.

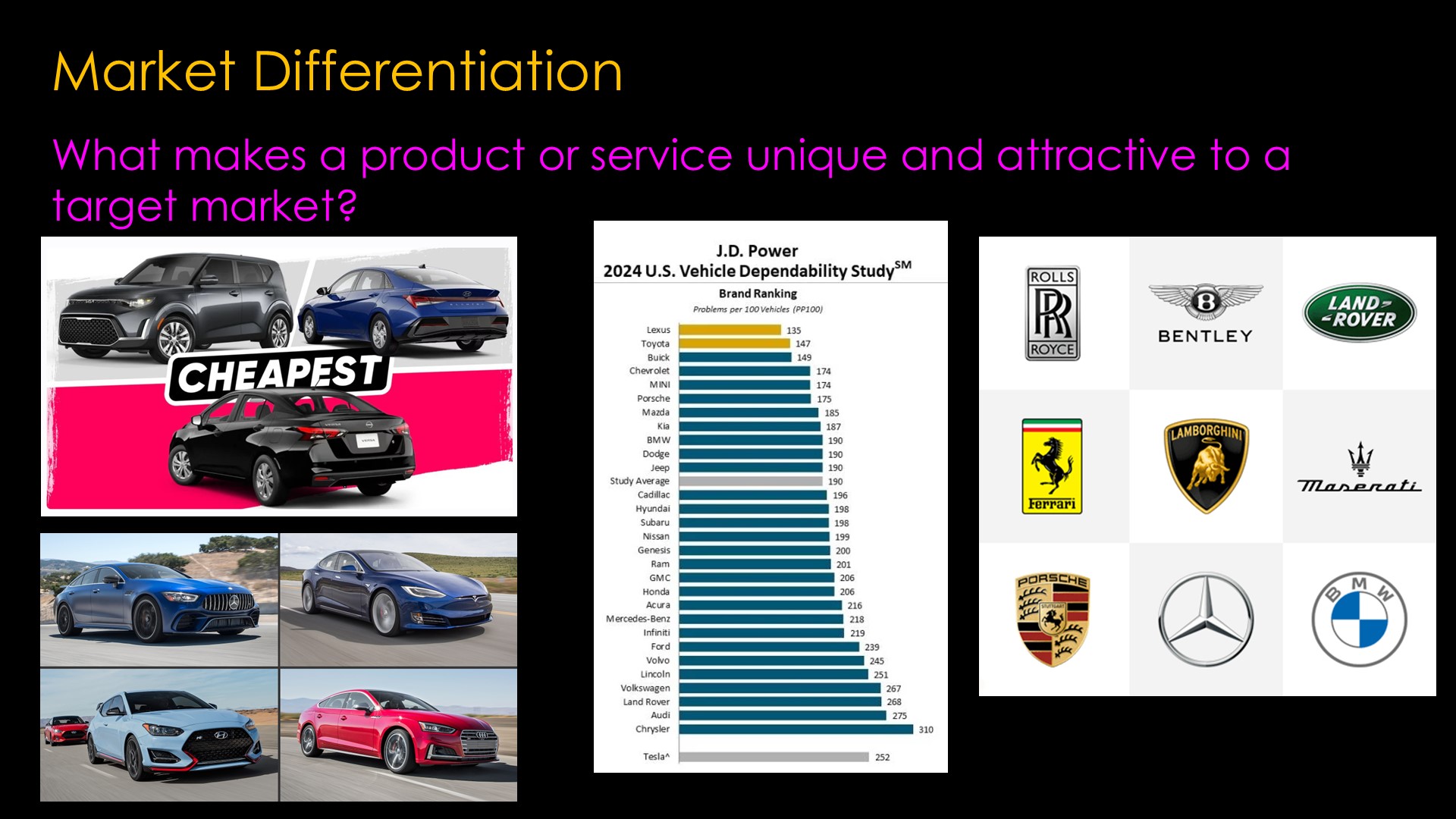

We also need to talk about differentiation, which is all about how figuring out what makes a product or service unique and attractive to a target market.

There are a bunch of different ways to differentiate. For cars, some do it on price, some do it on performance, some do it on reliability, some do it on brand reputation.

The point of differentiation is to be unique in ways that give you a competitive advantage.

And that's enough about cars, let's talk about rockets.

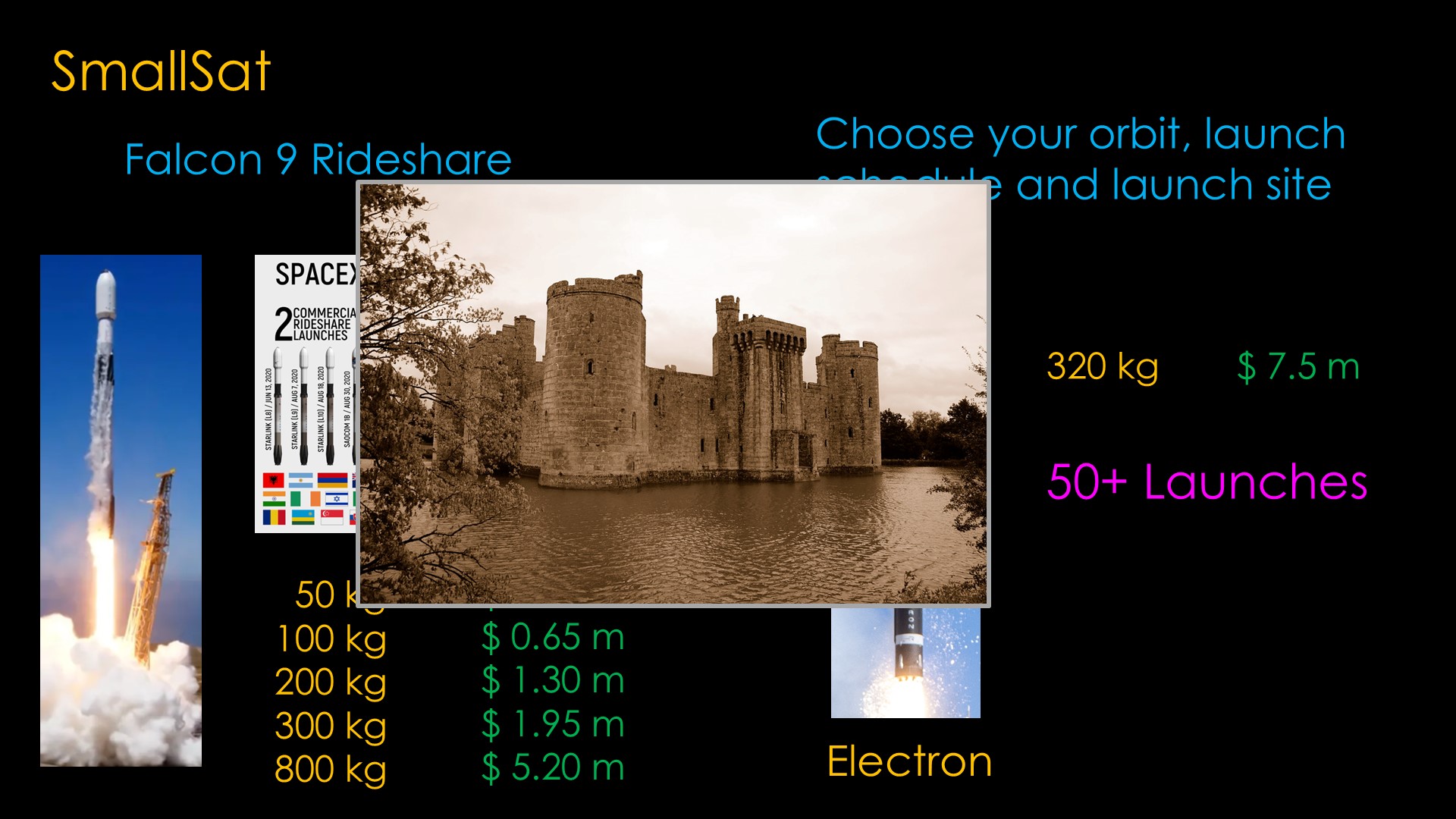

SmallSat launches are dominated by two players.

The first is Falcon 9 rideshare, which is up near 1000 satellites launched. It's cheap, cheaper than any other way to get small payloads into space. You can go from 50 kilograms for a third of a million dollars up to 800 kilograms for $5.2 million. It's a great bargain if you are okay with the location that rideshare flies to - generally a close to polar sun synchronous orbit. It flies two or three times a year so it's easy to schedule and there are a bunch of people who have flown on it so it's easy to get help with payload design and integration.

The product will be very hard to compete with. What could another company offer to differentiate themselves in this market? And would they ever make enough money to make the investment worthwhile?

This market belongs to SpaceX as long as they want to keep it.

But you probably noticed the caveat I made about the market. "if you are okay with the location that rideshare flies to" is that caveat, and you also have to be okay flying on the schedule that SpaceX defines.

If you aren't, then there's a different SmallSat market for customers who want control over the final orbit, launch schedule, and launch site. For them, a dedicated launch is the only thing that makes sense.

There were a number of companies targeting this market, but currently the market is owned by RocketLab's Electron rocket, which has over 50 launches and is launching around 15 times a year. It's pricey compared to rideshare - a little less than 4 times what SpaceX charges - and has a payload limit of only 320 kilograms, but it has been very successful. Interestingly, 14 of the electron flights have been rideshare flights - even with their small payload capability, there is still excess capacity on some flights.

If you want to compete with Electron, you need a factory, fully developed launch sites, and a good reason for customers who fly electron to fly with you. And you also need the extras that RocketLab offers as a full-service vendor.

This market belongs to Electron for as long as they want to keep it.

My point in discussing these markets is that they have significant barriers to entry. The competitor who has an ongoing business and a decent flight rate has huge structural advantages.

If there are significant barriers to entry, they are sometimes called "moats". If you want to compete, you need to figure out how to cross the moat.

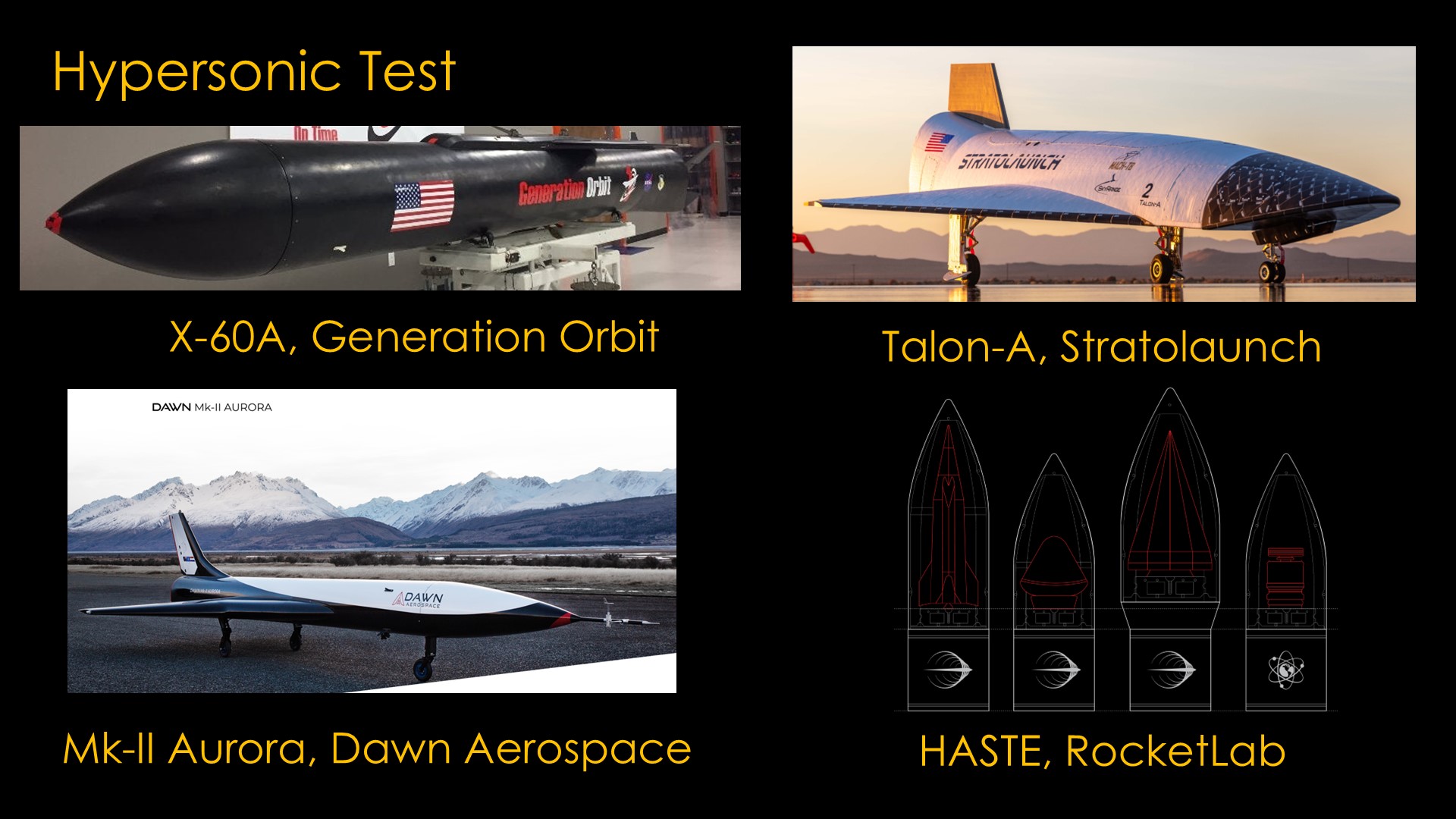

As long as we are talking about Electron, Rocket Lab has been flying an electron variant that they call HASTE that can fly in various configurations to support the testing of hypersonic vehicles. They will be joined by the X-60A from Generation Orbit and Talon-A from Stratolaunch, both air-launched vehicles.

Also in this group is the Mark II Aurora space plane from Dawn Aerospace, which I have talked about in the past. They are building a small rocket plane - only 5 meters long - that can access the edge of space with airplane-like cost and turnaround.

All three of these companies have pivoted from aiming at orbital solutions towards research at lower altitudes and orbits. I expect all four of these projects to do well as there hasn't been an attractive solution to the problem of hypersonic testing.

And we're going to move onto everybody's current favorite, constellations. There is one constellation that has impacted pretty much everybody in the US and in many other countries.

If you immediately said "Starlink", you are incorrect...

It's an array of 24 satellites way out at 24,000 kilometers and it's been in operation since 1993. It's the US Global positioning system.

In 1995 the Russians launched their equivalent, the GLONASS system, and the European Galileo system went online in 2019, each of those systems with 24 satellites in roughly similar orbits to GPS.

The point here is that constellations are nothing new. It's really about where you put them and how many you need.

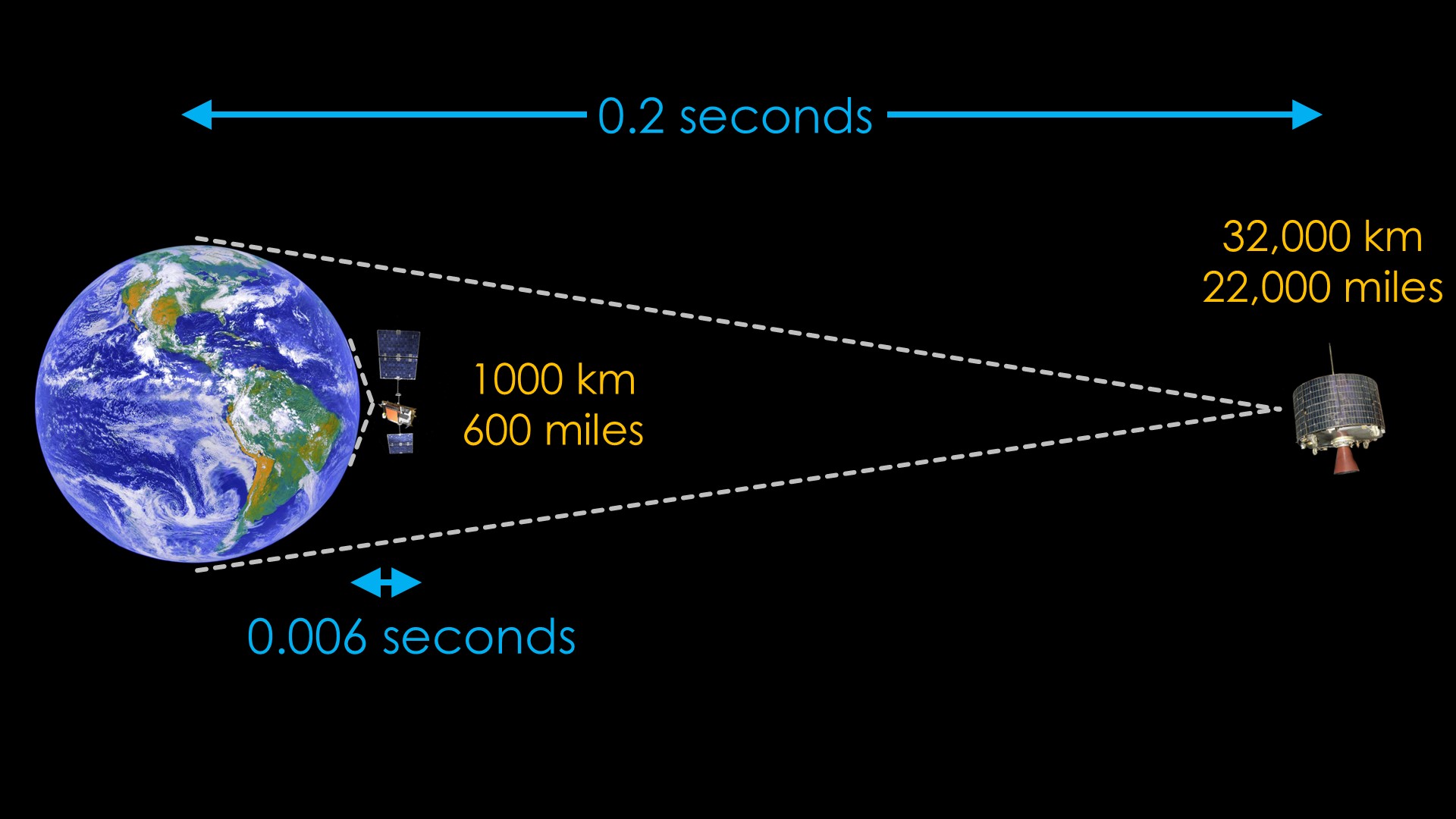

Geosynchronous satellites are roughly 3 earth diameters away, at 32,000 kilometers or 22,000 miles. That gives them a wide-angle view of earth, and they are able to see nearly a full hemisphere.

The downside is that the long distance means that you need a lot of power and there's a round-trip lag of 0.2 seconds, which means that time critical applications don't work very well - there is a noticeable lag.

You can reduce that lag by putting your satellite closer. At 1000 kilometers, the distance is only about 3% of the geosynchronous distance, so the round trip time is only 0.006 seconds, or 6 milliseconds. The downside is that you can only see a small part of the earth at any time, so you need a more satellites.

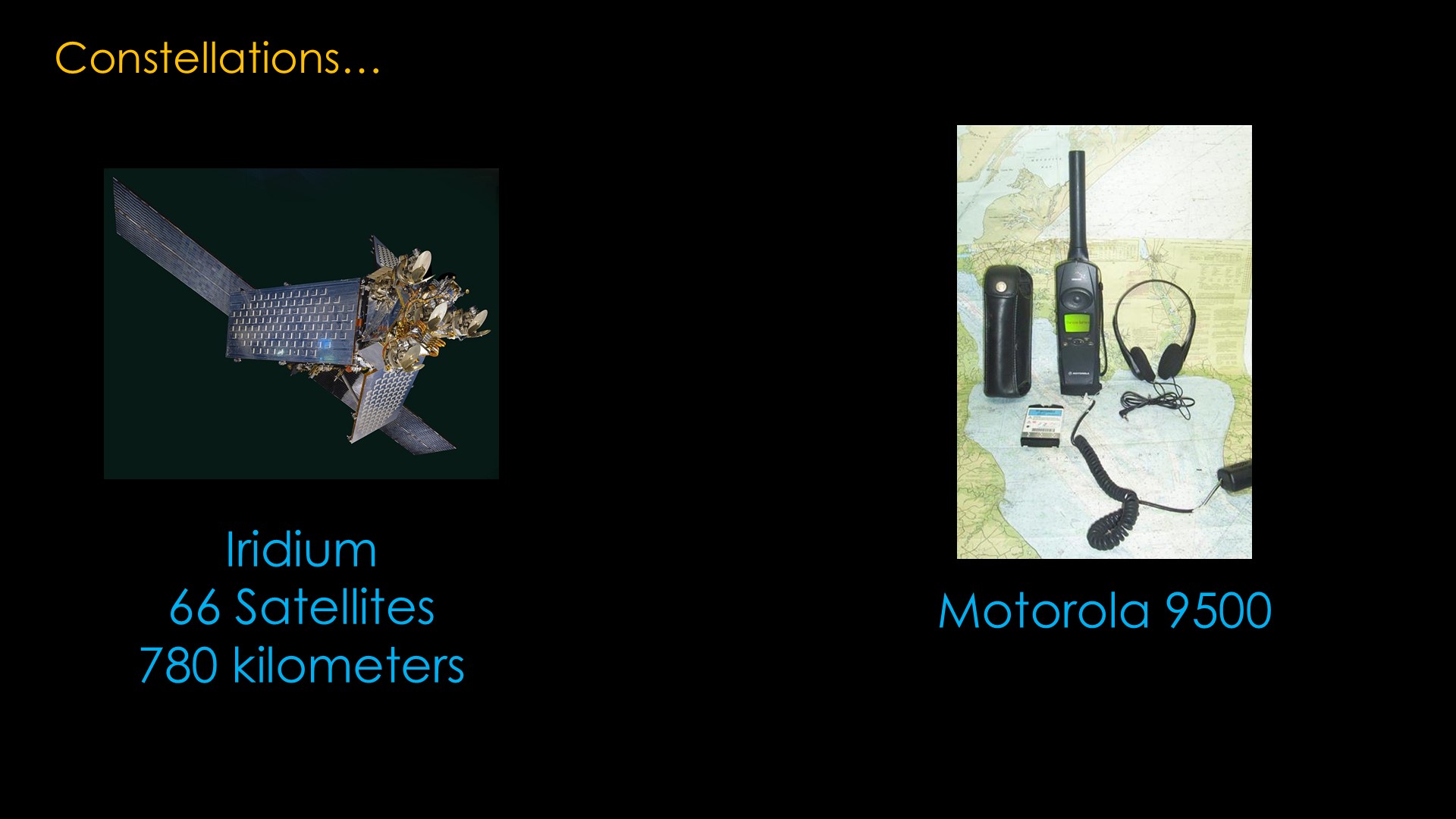

Near earth satellites are nothing new. In the 1990s there were plans for low cost satellite phone and internet constellations.

The Iridium constellation lived at 780 kilometers and went active in 2002, at a cost of about $5 billion, close to $9 billion in 2024 dollars.

Iridium went bankrupt and then - since the satellites were still in orbit and operational - was reorganized and became a communications provider for areas where other options did not work well.

This left most of the industry unexcited about this business...

But if you're launch company that has a partially reusable launcher, suddenly it becomes a lot more possible. And if you are going to build thousands or even tens of thousands of satellites, they will end up being a lot cheaper. And they don't have to be perfect as you have a lot of redundancy and since they are only going to last a few years, you'll be constantly launching to replace them with newer versions.

And suddenly the impractical becomes practical.

Starlink is at around 7000 satellites, headed for 10,000 for their first constellation and then going beyond that.

But Starlink isn't the only company in this market. And no, the other company is not the one you are thinking about - it's OneWeb, with a constellation of about 650 satellites at 1200 kilometers. OneWeb also went through a bankruptcy, it had 36 satellites that were supposed to launch on a Soyuz but were impounded by the Russian government, and it finished its constellation launching on Falcon 9. It's currently owned by Eutelsat, a French company that owns and operates many geosynchronous satellites.

At this point I hope you are asking yourself why a little company thinks the can compete against the Starlink Juggernaut, and the answer is fairly simple.

They aren't in the same market.

Starlink is aimed primarily at consumers, and users will deal with slowdowns and other issues due to the amount of usage on the network.

OneWeb is aimed at professional applications, and you can buy performance guarantees from them - if you need a specific data rate all the time, they will guarantee that you get that data rate.

Time to discuss the other company you were thinking about.

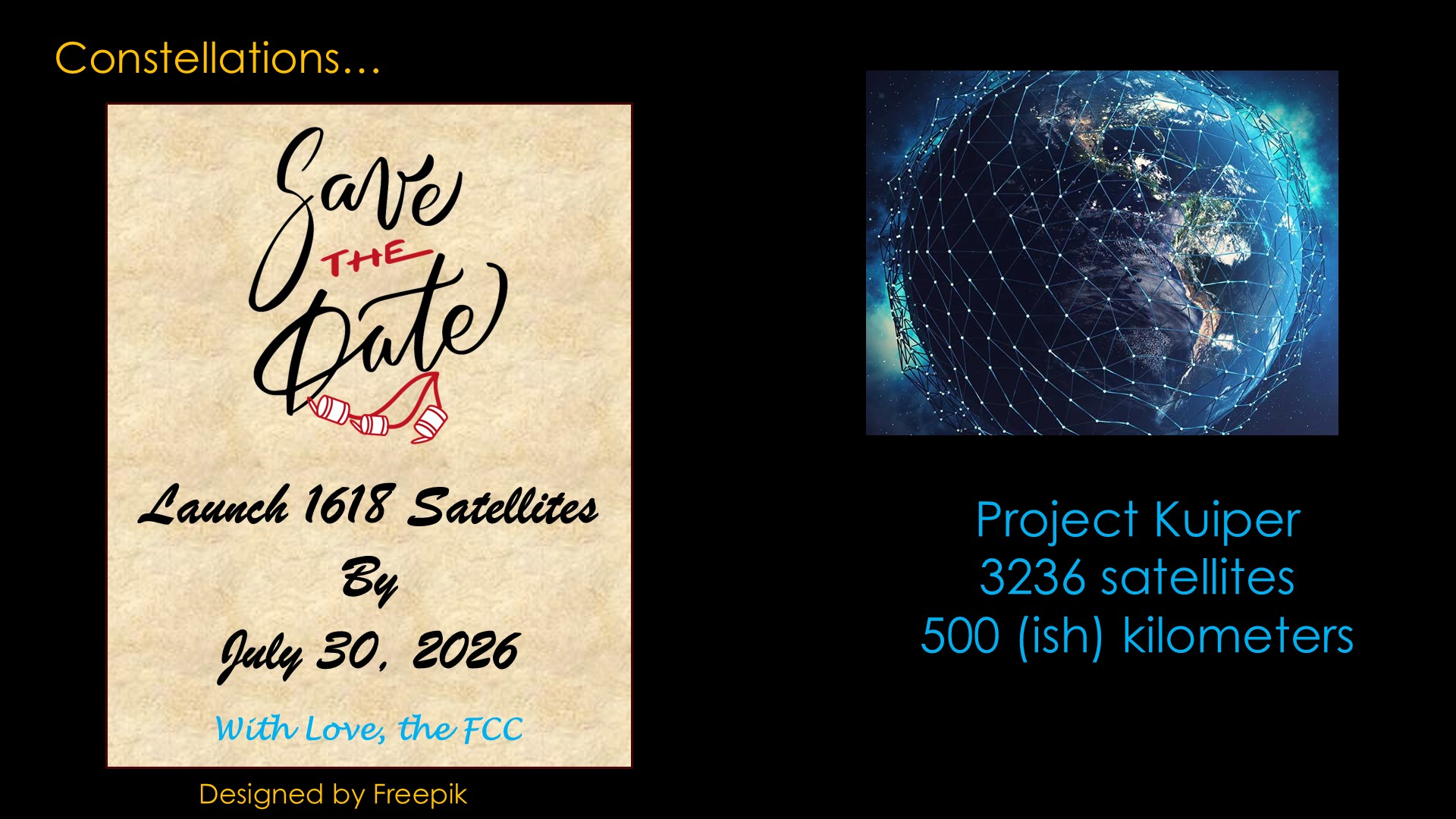

Amazon decided that they needed to compete with Starlink and came up with Project Kuiper, which is planned to put 3236 satellites at about 500 kilometers of altitude.

Because the frequencies that the satellites use to communicate with the ground is a limited resource - what the satellite folks call "spectrum" - there's a rule to ensure that you actually have to be using the spectrum you have been given.

When Amazon got their initial FCC approval in 2020, the FCC send them a save the date card to remind them that they had to launch half their constellation in 6 years.

That presented a real problem. Not only does Amazon not own a launch company with the capacity to do that many launches, it wasn't clear if there was a single launch company that could take on the contract.

And therefore they just bought all the launch capacity they could find.

They bought 9 Atlas V launchers, all the remaining Atlas V that ULA was planning to build.

They bought 38 launches on ULA's future Vulcan rocket.

They bought 18 launches on the future European Ariane 6 rocket.

And they bought 12 launches on Blue Origin's New Glenn Rocket.

These contracts were viewed as a huge windfall for all of these organizations, leading to celebrations. Three new rockets had suddenly become viable, with initial launches and likely future launches to finish the constellation and replace satellites that would deorbit.

Two rockets didn't get an invite to the party.

The first is Rocket Lab's Neutron. That could have been due to the longer timeline for Neutron, or it could have been because Rocket Lab Founder Peter Beck doesn't like signing contracts on rockets that don't exist. I suspect that rocket lab has been in negotiations with the Amazon team for future launches, as constellation launches is what Neutron is designed for.

The second is Falcon 9. It's not a secret that there is no love lost between Bezos and Musk, and I sometimes call this the "anyone except SpaceX" market.

But there was a bit of intrigue there. Amazon stockholders filed a suit claiming that the Board of Directors acted in bad faith, allowing Jeff Bezo to negotiate launch contracts from the Amazon side that benefitted him personally as the owner of Blue Origin. It also claimed that Falcon 9 launches would have been cheaper than the Atlas V launches Amazon bought.

Since then, Amazon has signed a contract for 3 launches on Falcon 9.

Who is going to dominate this market?

Rolling the clock forward to early 2025, all we see are problems...

Amazon launched two prototypes in late 2023 on an Atlas V, which means there are 8 launches remaining. There are reports that Kuiper is ready to start real launches in 2025, and Atlas V will be the first launcher to step up. But that is all the Atlas V that are currently available, though if Boeing cancels Starliner there could be 6 more available.

The three new rockets have combined to fly 4 missions in total.

Vulcan is in the best position to fly more often, but they have a previous engagement with the US Department of Defense launching satellites from them and a big backlog. The space force is not happy with the Vulcan delays and there is a pending contract for future launches that ULA really needs, and it seems unlikely they can fly enough to cover both the DoD and the Kuiper launches. More on that later.

ULA also has the issue that they fly on Blue Origin's BE-4 engine and are limited by the number of engines Blue Origin can provide.

Ariane 6 is also a few years late, and they have a large backlog of European payloads that they need to work through. There is currently one Kuiper launch scheduled for late 2025, but that is all. It is very hard for Ariane to scale up their launch cadence because it requires agreements to be negotiated across multiple countries.

New Glenn successfully flew in early 2025, but their plans to scale up their launch rate are unrealistic, and Blue Origin celebrated their success by laying off 10% of their workforce.

Ariane 6 can't ramp up. New Glenn might surprise me, but I think 2 additional launches in 2025 would be a hard goal to reach, which means the market is ULA's to lose.

That assumes the market is going to keep existing. The guess is that those 8 Atlas V launches gets them 200 ish satellites in orbit, and the 3 new rockets won't be able to add a lot to that.

The big question is what the FCC deadline means, and I don't think anybody really knows. There is speculation that the FCC will extend the deadline if the company is showing momentum towards completing the constellation, but does 400 satellites with most of them launched on a rocket that isn't flying any more good enough? Unknown, and that's not factoring in the current government upheaval and the fact that satellite regulations are an international thing.

There is one rocket that could push them much closer to that 1618 satellite goal, and that is Falcon 9. And if SpaceX manages to get Starship delivering the new and bigger Starlink satellites, that might leave them with a lot of excess capacity that they could devote to Kuiper.

The only thing I'm fairly sure of is that Kuiper is really, really behind. It took SpaceX about 4 years to get the first half of the starlink constellation - 2200 satellites - operational, and then a bit over a year to get the second half up.

What happens here? I have no real prediction. The right business decision is to contract to fly as many launches as possible on Falcon 9 because that is the best way to demonstrate commitment to the FCC. It would actually likely be cheaper than the current plan. If you force me to guess, however, I think that Amazon is going to try to launch what they can with their existing contracts and then lobby their way into an FCC exemption.

In summary, Kuiper has a chance to be a big launch market for somebody, with ULA the most likely winner, but the market also might evaporate.

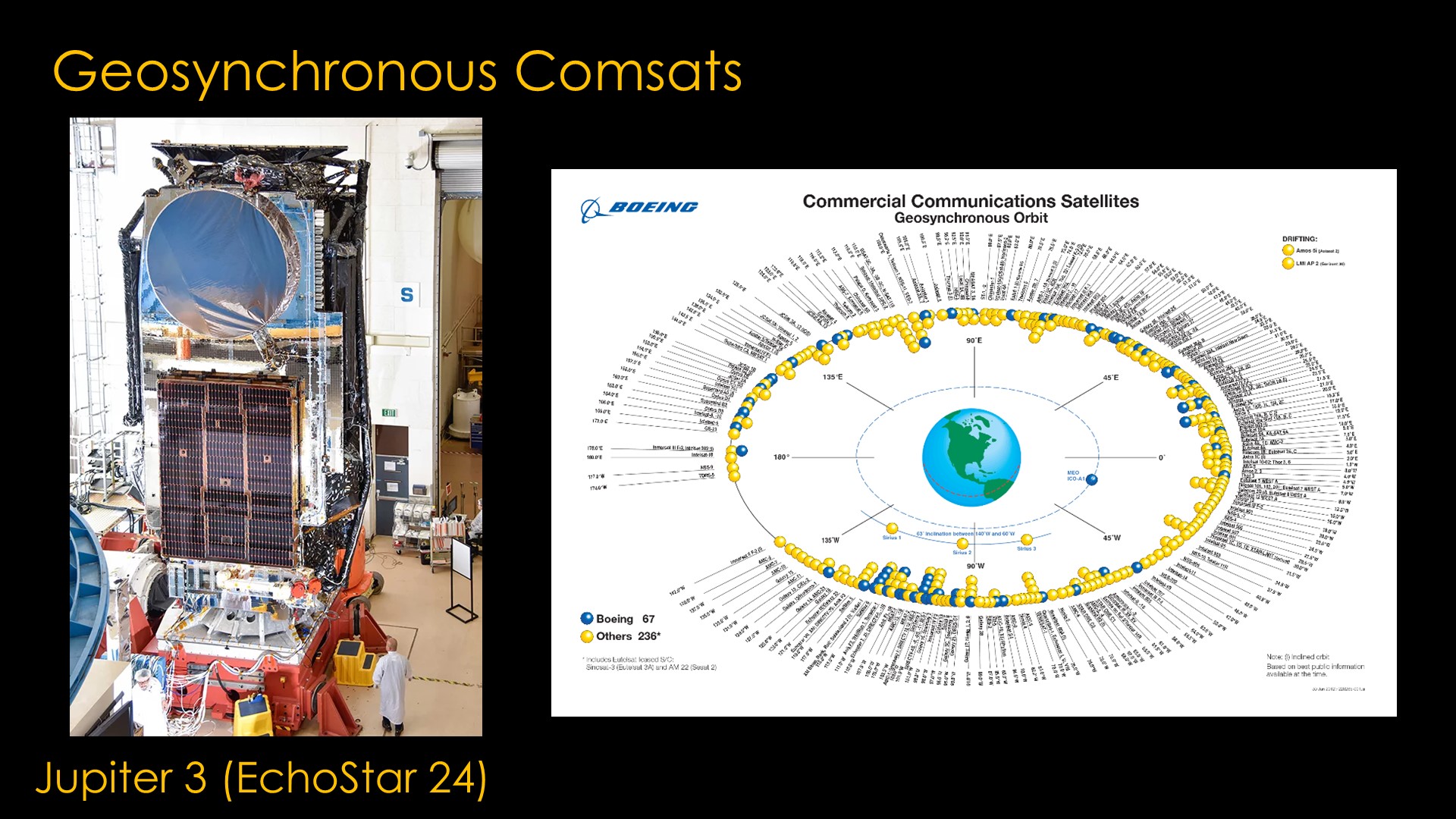

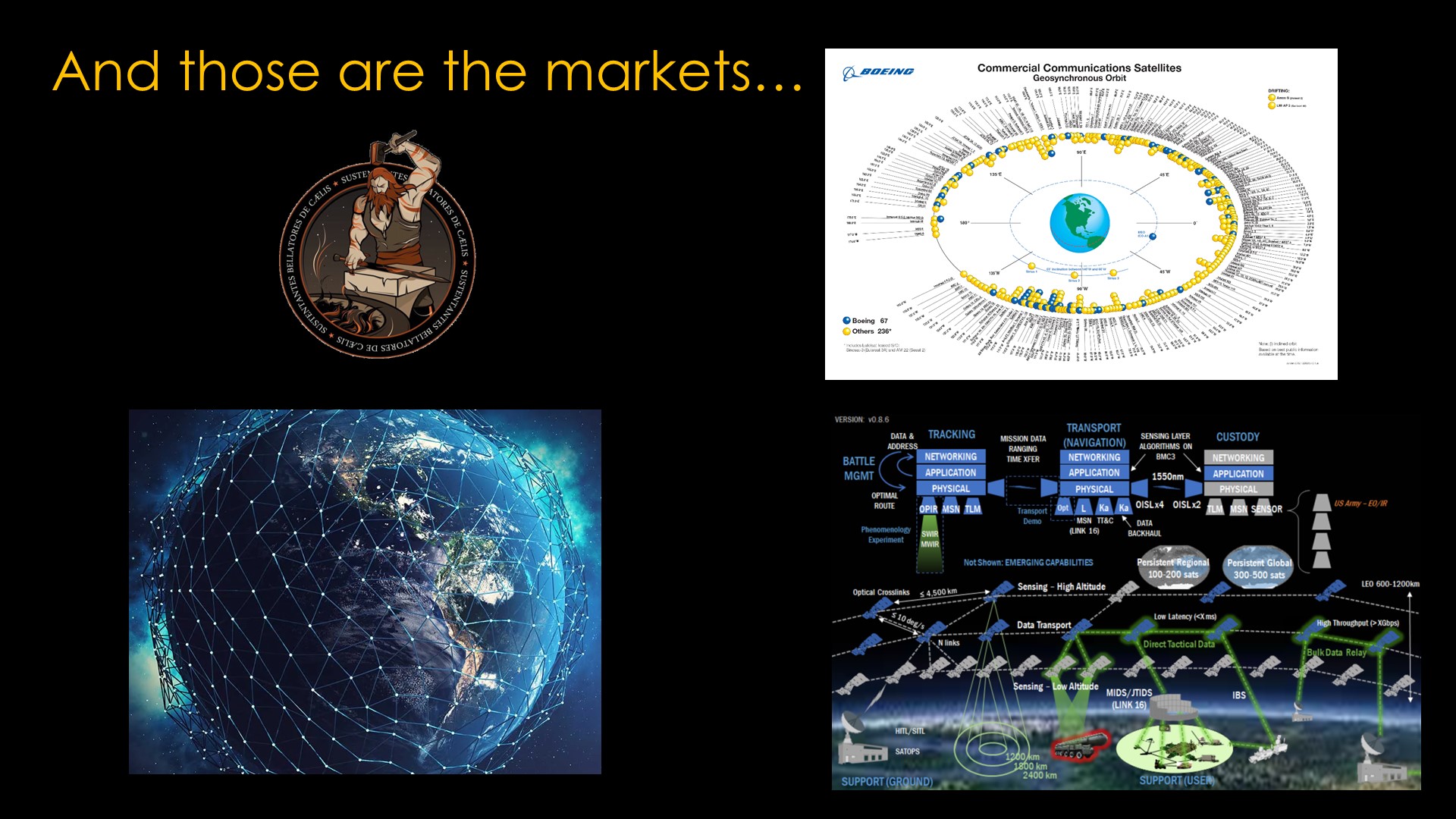

The next market is geosynchronous communication satellites.

The satellites need to be powerful for their signals to be easily received at earth and it takes a lot of energy to get to those orbits, so these satellites are big, complex, and very expensive - the newest ones cost $300 - $400 million.

It's fair to say that - along with military launches - these satellite launches built the commercial launch industry.

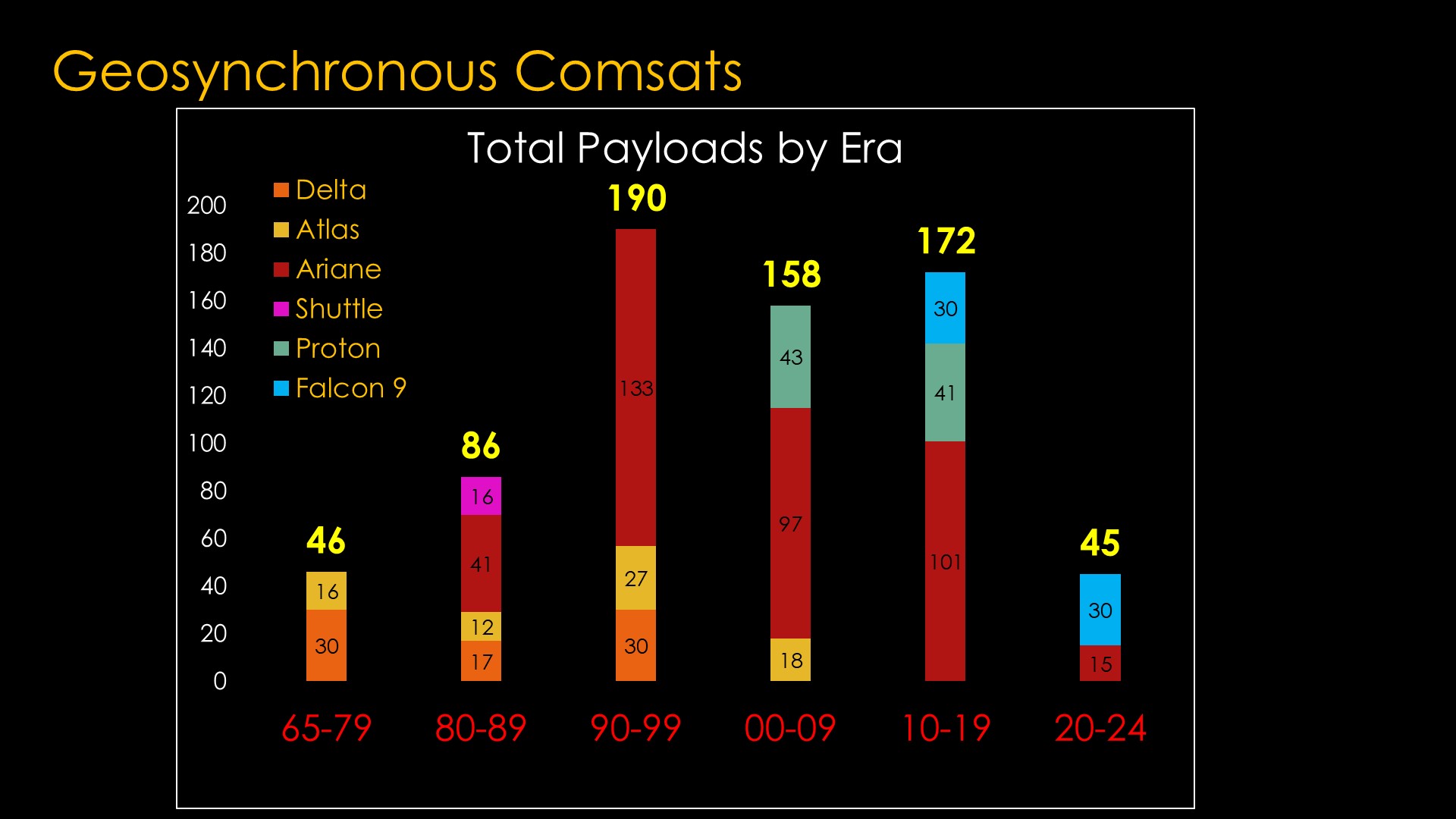

The success is very clear from this graph - the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s were great decades, with Ariane doing a ton of launches.

But in the first half of this decade, we see only 45 launches, roughly half the rate of the previous decade...

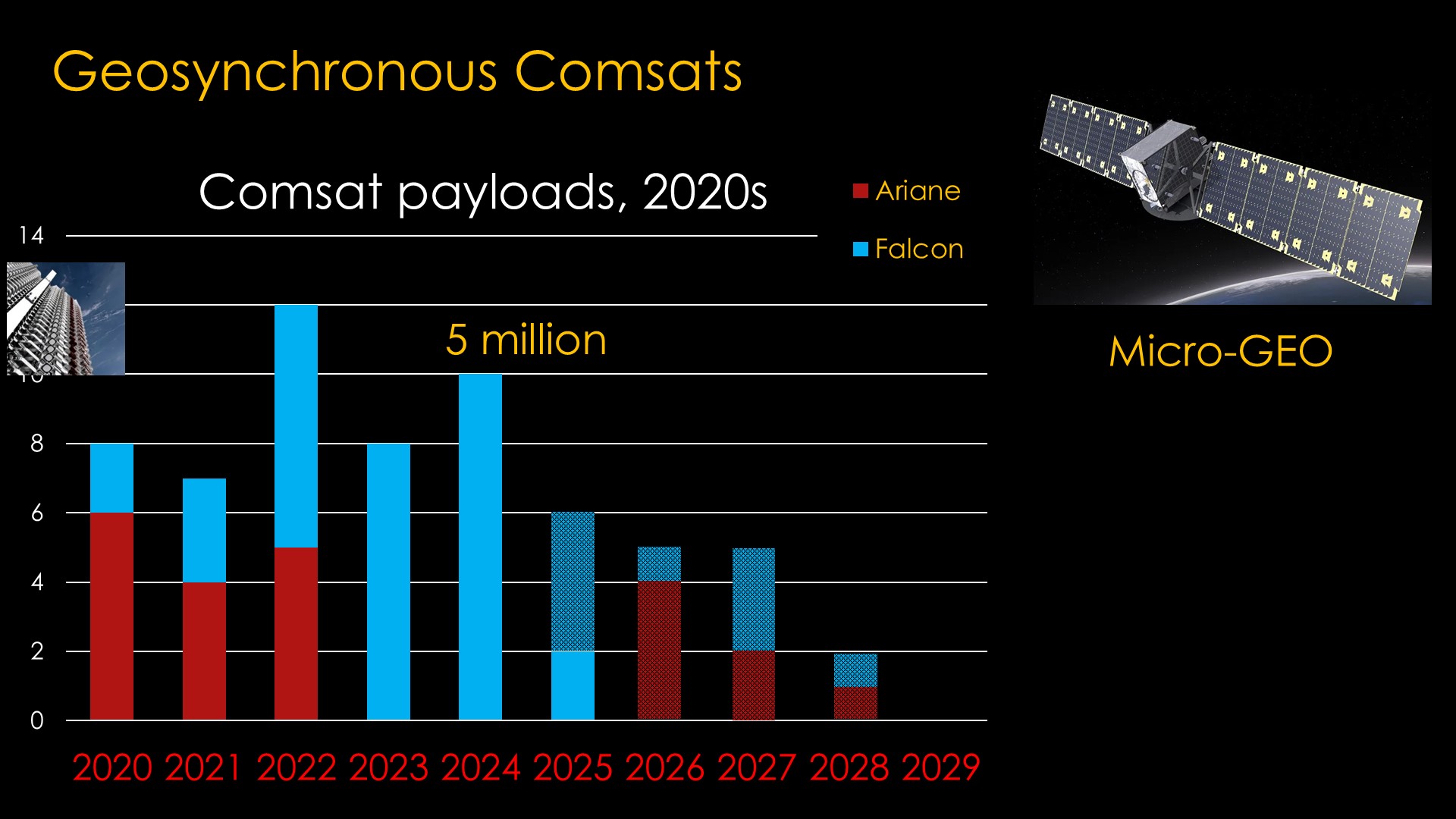

Zooming in on the 2020s, we see a few things.

Ariane disappears after 2022 as they ceded the market entirely to SpaceX when they closed down the hugely popular Ariane 5 launcher before Ariane 6 was operational, and that means for 2023, 2024, and 2025, the only rocket launching these payloads was Falcon. This was unexpected as Ariane had been very careful to keep flying a previous launcher when a new one was coming on line, but for some reason they didn't do this for Ariane 6.

If we look at projected future launches based on the announced launch contracts, we see the launch number continuing to trend down, though there are likely more satellites that have not yet signed launch contracts.

There are two big trends going on in this market. Starlink went operational in 2019 and as of early 2025 has about 5 million subscribers, and there are other constellations either operational or in the planning phase.

Nobody knows how big of an effect those constellations will have on the success of geosynchronous comsats.

There has also been the introduction of "micro-GEO" satellites, with masses as low as 400 kilograms, roughly one tenth of the mass of most geosynchronous satellites.

I expect that the market will take a "wait and see" attitude for the time being, and that means there will be few launches.

How does that affect the launchers?

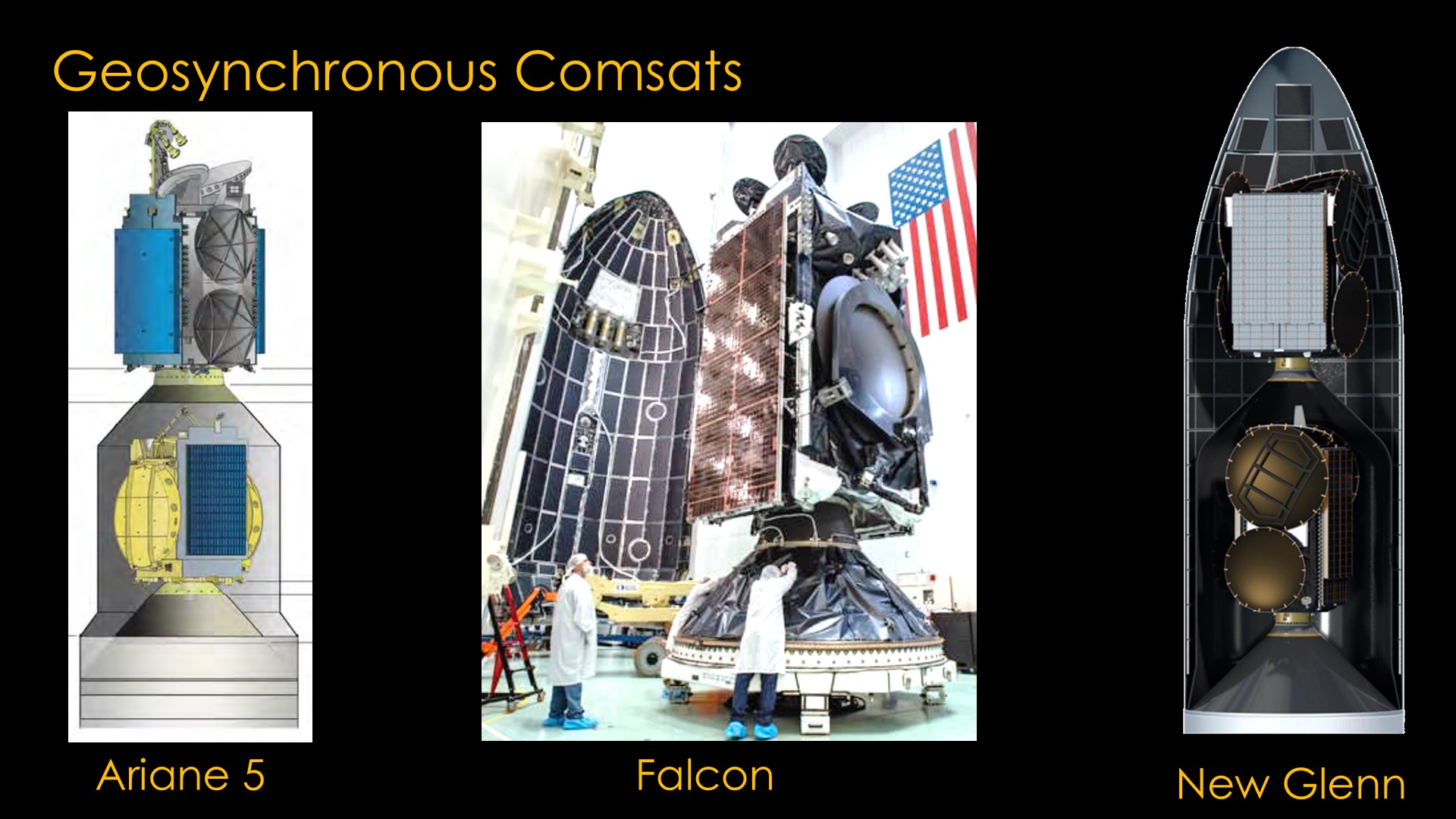

There are three contenders for this market.

The current leader is SpaceX with the Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy depending on the customer's payload requirements.

SpaceX follows a simple approach - put the satellite in the fairing, launch it, and you're done.

Ariane took a different approach. They realized that geostationary satellites are all in an identical orbit and that it's cheap to get to a specific spot once you are in the right orbit. They therefore designed a rocket that is oversized for the payloads they want to carry, one that carries one normally-sized satellite in the upper berth and a slightly smaller satellite in the lower berth. That gets them a 2 for 1 in terms of launch cost, and was hugely successful when they were doing a lot of launches per year.

Blue Origin decided to "out Ariane Ariane", and when they designed New Glenn they made it big enough to carry two full-sized satellites.

The problem is that the market has shifted. With the lower launch rate and more competition, it's going to be much harder to fill both of those berths. For customers, they can fly with Falcon pretty much whenever they want, where with Ariane 6 or New Glenn they need to either wait and hope a second payload shows up or pay a much higher price to launch on an oversized rocket. That's assuming that New Glenn has the payload that Blue Origin hopes it will have.

That gives Falcon - which already has a big advantage because it flies so often - another advantage. I therefore expect that SpaceX is going to get the bulk of the market, Ariane will pick up the rest, and Blue Origin will find it hard to get any flights.

The Dark Horse is ULA's Vulcan. ULA had ceded this market to Ariane because they couldn't compete on price, but if Vulcan is launching a lot for Kuiper, Vulcan might be cheaper here than Ariane 6.

The next category is US Government launches and we'll start with national security space launch.

NSSL doesn't have a program logo as far as I can tell, but does have nice mission patches. This one from NROL-55 translates to "Supporting the warriors from the heavens".

NSSL is in the midst of some big changes and it's one of the reasons I wanted to discuss these markets.

NSSL is breaking their launch needs across two separate markets. The first one I'm going to call "NSSL Classic".

In the decades before SpaceX showed up, the way it worked was that the air force followed a very simple procedure to define what missions they planned on flying and to put out a request for proposal to all the US launch companies.

Which, since 2005, meant United Launch Alliance as they were the only US launch company that could launch the air force payloads. The reason for that involved industrial espionage and some air force interference that was probably not legal. See my video "spies, allies, and enterprise - the strange story of ULA" for the whole story.

ULA would agree to do the launches for an exorbitant amount of money, and that was just the way things worked through about 2018, though after some legal nastiness the Air Force agreed to toss SpaceX 7 Falcon 9 payloads and 3 Falcon heavy payloads.

This era was known as "phase 1" of NSSL.

The air force was not surprisingly receptive to saving a lot of money flying on SpaceX rockets. ULA knew that the phase 1 world no longer existed, but their current two-rocket solution was far too expensive and meant that they might not do well in the phase 2 competition.

Their solution was to say goodbye to their two existing rockets and debut a new rocket named Vulcan.

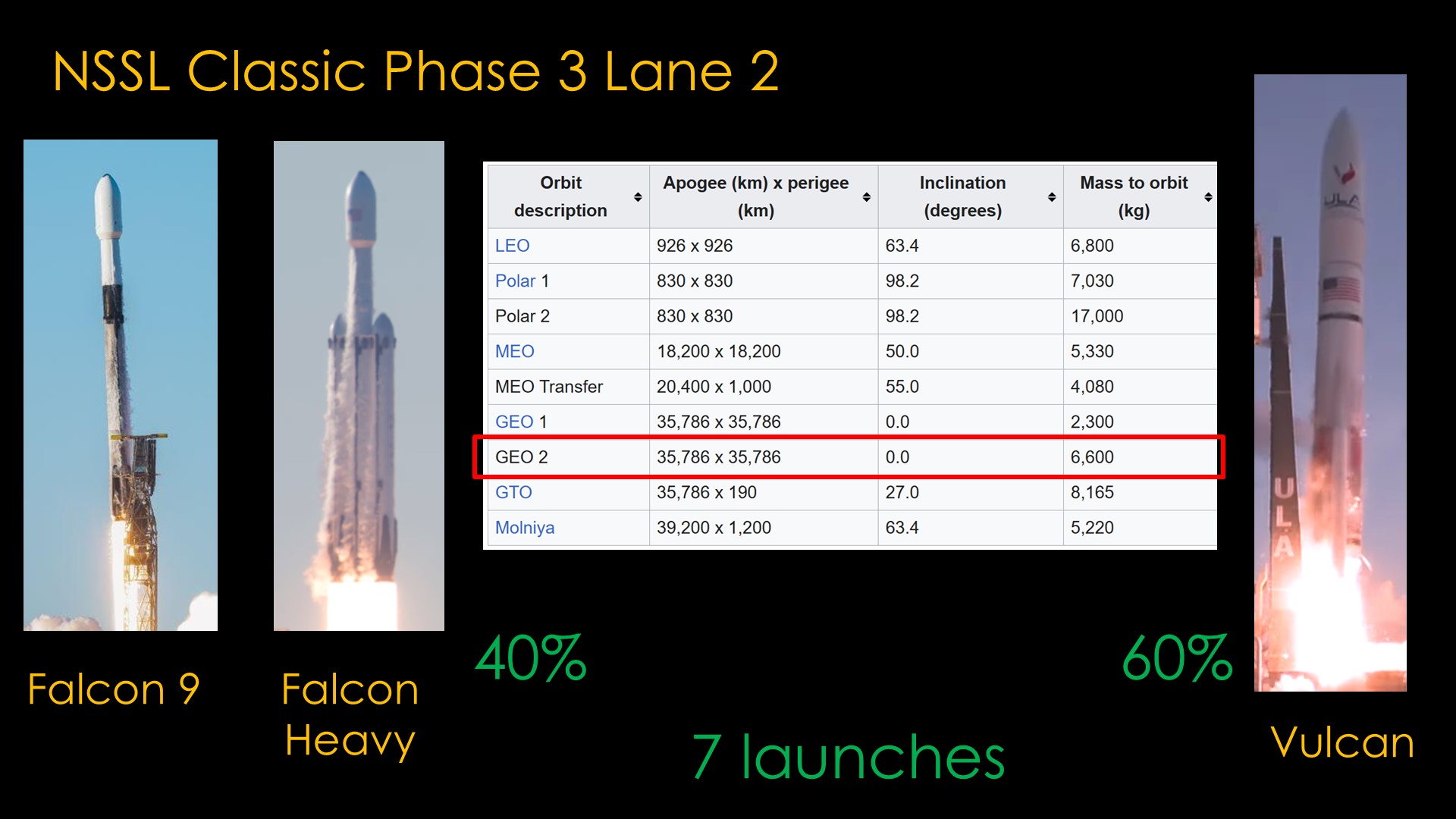

Vulcan can reach all the orbits that the Air Force required, including the requirement to take a 6.6 ton payload all the way to a geosynchronous orbit. This is really, really hard to do and to bid phase 2 you have to be able to do it. Bidders have to cover all orbits because the air force was concerned that companies might ignore the hard orbits and just bid on the easy ones.

This program included bids by Northrup Grumman with their OmegA rocket and Blue Origin with New Glenn, and the air force ended up awarding 60% of the launches to ULA and 40% to SpaceX.

SpaceX has flown 4 of their launches, and the Vulcan certification to launch NSSL payload is expected in the first few months of 2025.

The current schedule shows SpaceX launching 15 missions in 2025, all on the Falcon 9, and 3 launches in 2026, all on Falcon Heavy. That seems well within their capability.

ULA is scheduled to fly 13 missions on Vulcan in 2025 and 5 missions in 2026, with a further 10 phase 2 missions unassigned to a launch year. There is essentially zero chance that Vulcan is going to fly 13 Vulcan missions in what remains of 2025. Some of those missions might get pulled away from ULA and given to SpaceX. Remember that ULA needs to figure out how to launch Atlas V and Vulcan missions for Kuiper and Vulcan missions for NSSL, mostly from a single launch pad on cape Canaveral space force station in Florida.

That sets the stage for New NSSL...

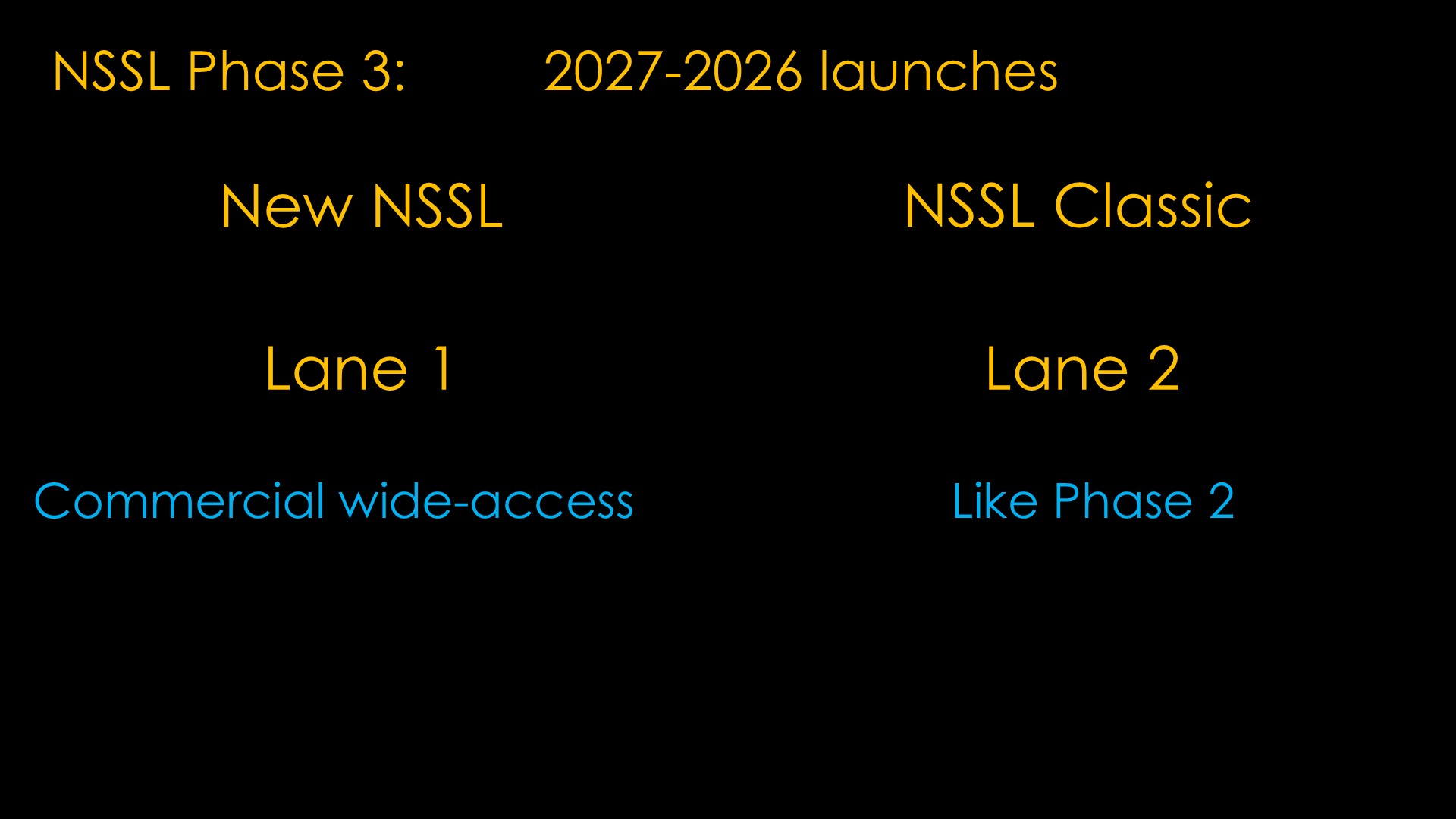

NSSL phase 3 is a brand new world.

There is the NSSL Classic side, which the space force calls "Lane 2", and there is the New NSSL, what the space force calls "Lane 1", which intended to be a very competitive market with opportunities for lots of launch companies.

The big push for this two-tier approach comes from the realization that the space force is moving towards a constellation-based approach and that means more launches and more tolerance for launch failures. And there's a hope that this will spur competition and push the government launch prices down closer towards the commercial launch prices. As a reference, SpaceX will charge roughly double their commercial comsat launch price for NSSL launches.

These are two very different market approaches so we'll cover them separately.

NSSL Classic Phase 3 lane 2 was originally defined the same way as phase 2, and the only open question was whether the 60/40 split would reverse, with 60% going to SpaceX and only going 40% going to ULA.

But Blue Origin sent some money off to lobbyists, and a surprise revision showed up. Lane 2 will now pull 7 missions out of the overall set of planned missions and allocate them to the company that comes in third. There will be 5 missions launching GPS satellites into medium earth orbit, and 2 mission taking payloads all the way to geo orbits.

The first and second place providers are expected to handle about 50 missions in total.

This change puts New Glenn into the competition. I think it is unlikely that they will finish first or second, but there's a very good chance they get third as there are no other competitors.

My New Glenn model suggests that they cannot meet the requirements of 6.6 tons direct to geosynchronous orbit with their current model, and will require either the third stage that they have talked about in the past or some sort of kick stage. That might be a role for Blue Ring, which could carry a satellite from geosynchronous transfer orbit out to the final geosynchronous orbit.

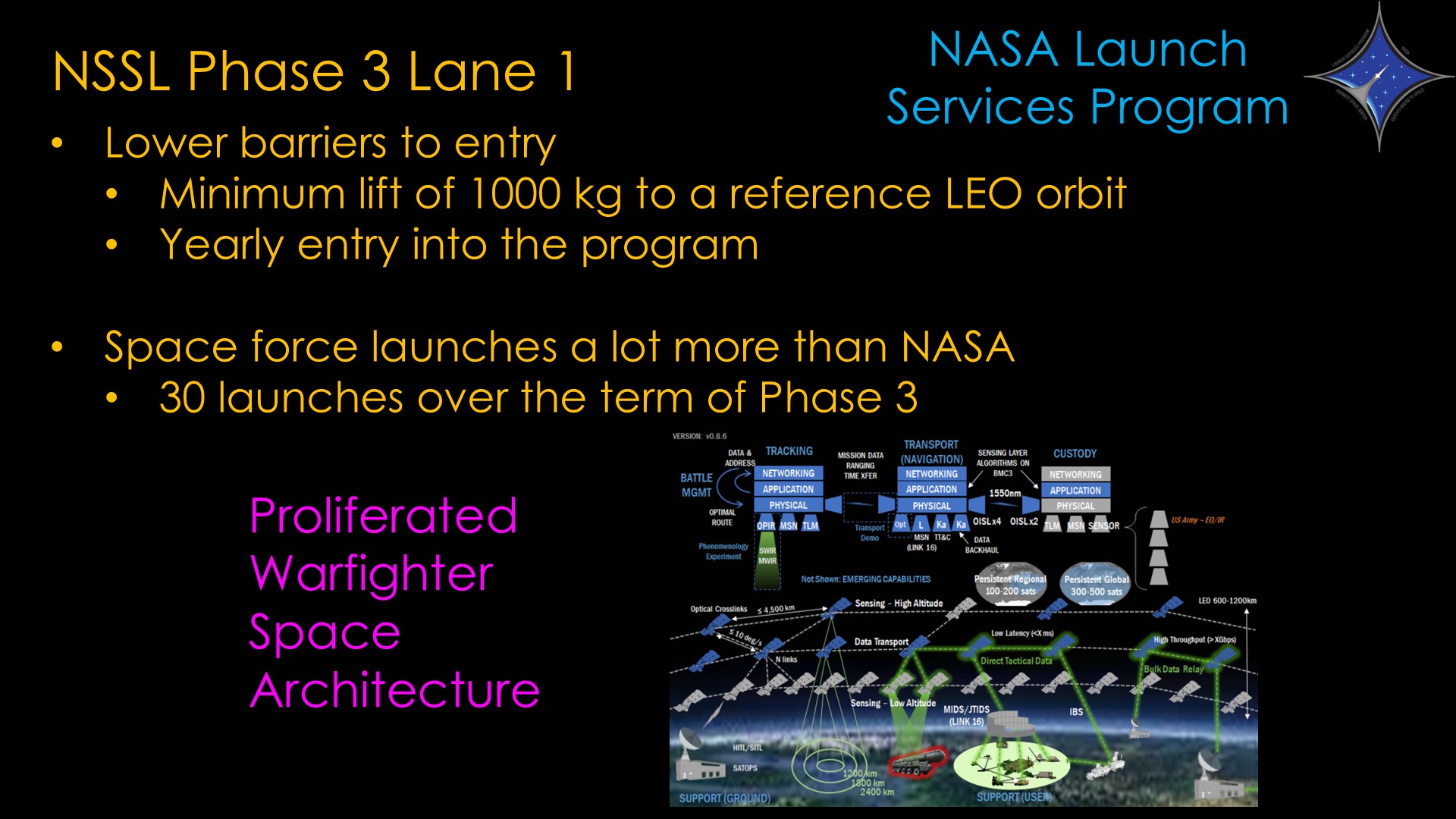

The new thing is NSSL Phase 3 Lane 1, and it's a big deal.

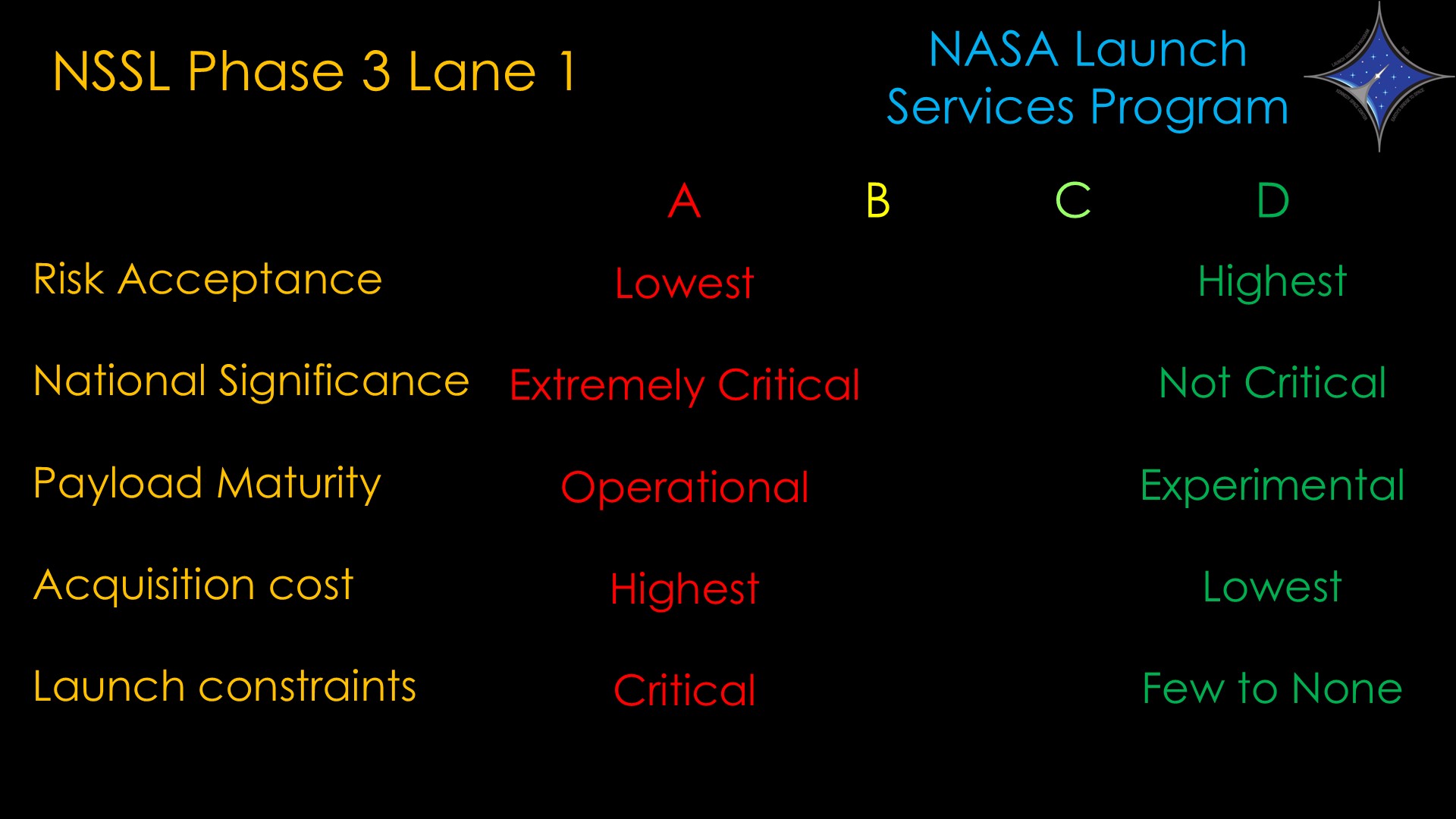

It is modelled after NASA's Launch services program, the method that NASA uses to procure launch services for uncrewed missions. NASA has been doing this for 35 years and it has been quite successful and is therefore rarely mentioned.

The important realization that drove the NASA program is that payloads and programs are very different.

There are some programs - NASA would call them "flagship programs" - like James Webb Space Telescope that are really important and expensive and therefore have very low risk acceptance. They are Class A programs.

There are other programs - such as NASA's escapade Mars probes - that are cheap, with an overall budget of $79 million. They are small and innovative but you can't afford a Class A launch for them. They are Class D programs.

And then there are class B and C programs, which rank somewhere in the middle.

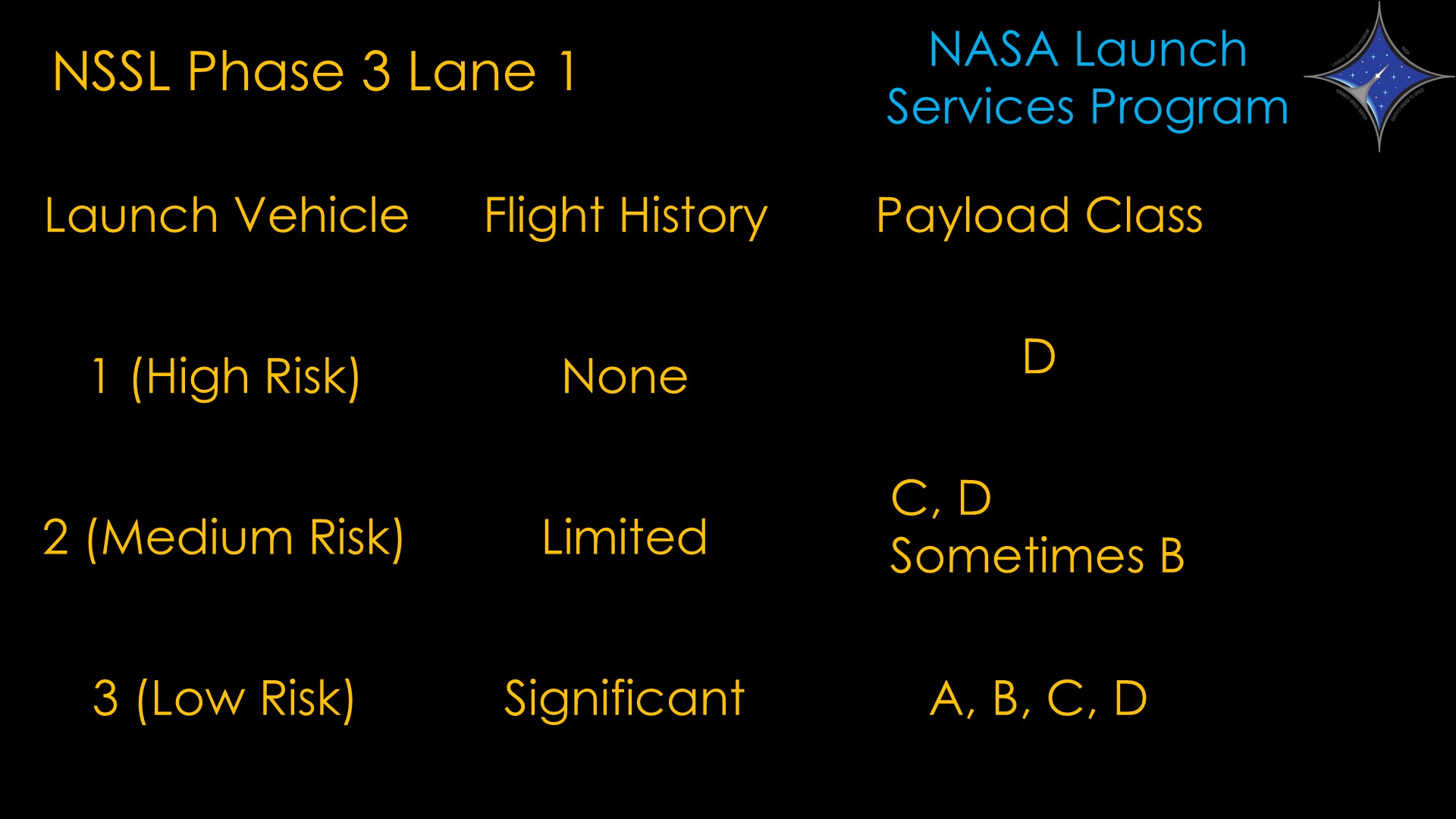

A similar ranking system is applied to the launch vehicles.

Vehicles with no flight history fit in the high risk category, and are only allowed to fly payload class D missions. This may seem like a bad deal for the creators of those payloads, but those programs do not have the money to fly on more expensive vehicles. This is how New Glenn was scheduled to fly the Mars Escapade payload on its first flight. I think it would be clearer if they called this category "low reliability", but nobody asked me.

Vehicles with limited flight history can fly class C or D payloads, and sometimes B, and those with significant flight history can fly all classes of payloads. There are significant conditions that a launch vehicle needs to meet before it can move to a lower risk category.

Lane 1 is significant for a couple of reasons...

The first is that it has lower barriers to entry - you can show up with a rocket that can do 1000 kilograms to a reference LEO orbit and still join. And you have a chance to enter the program yearly and compete for programs that will be awarded that year.

The second is that space force launches more often than NASA; for phase 3 they are talking about 30 launches.

Two things to note.

The first is that the Space Force is moving towards what they call the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, and that will involve lots of satellites in low constellations. That means that the number of launches might go up in the future.

The second is that the existence of Lane 1 will put pressure on Space Force to pull missions out of lane 2 and move them to lane 1, as the process is much easier and the launch will likely be cheaper.

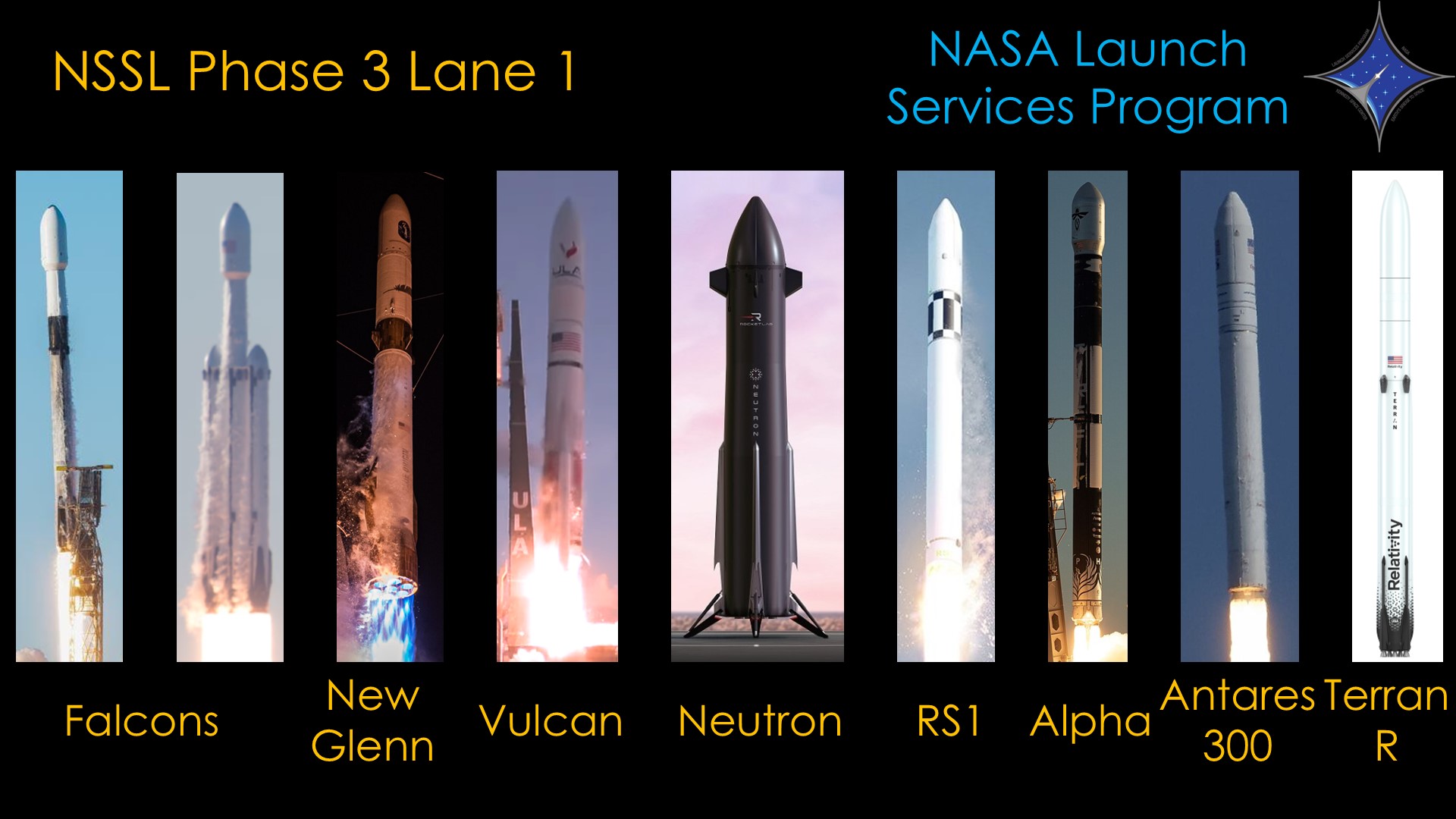

The first round of Lane 1 has the usual suspects - those who were already in the Lane 2 competition and therefore could easily qualify.

But I expect that we will also see Rocket Lab's Neutron, ABL's RS1, Firefly's alpha, Northrup Grumman's Antares 300, or relativity's terran R.

And I've heard there might be a new big rocket that SpaceX is working on. That might work for lane 1 as well.

The is the most open market and therefore will be the most competitive one. Lots of opportunities here but it's going to be really hard to compete with SpaceX because the Falcon flight rate will be so high - at least for the payloads that need to be low risk - but there will be chances for the smaller players on the missions where higher risk is okay.

I'm not going to talk about NASA's program because it's essentially the same thing and the same considerations apply.

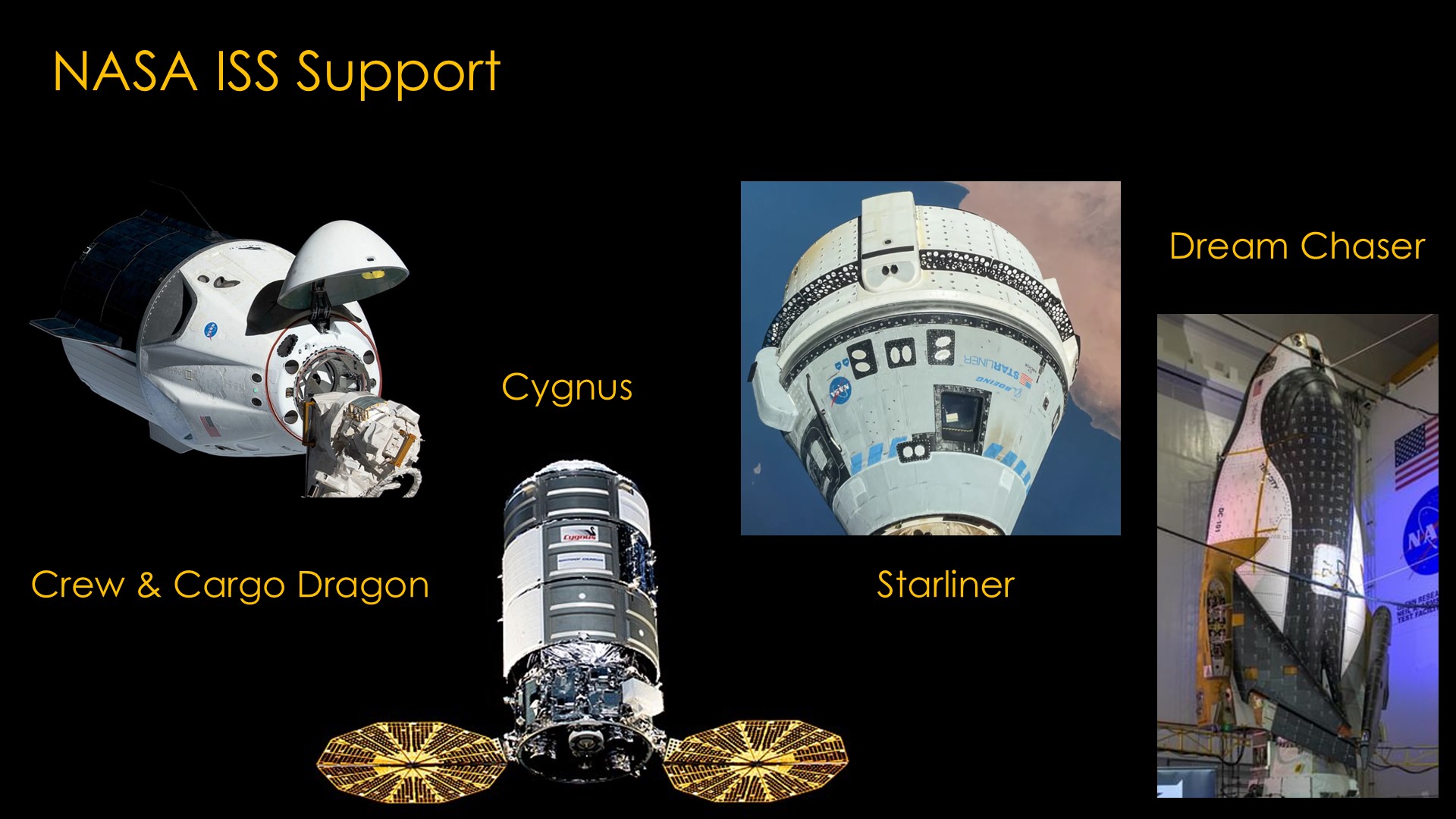

NASA ISS Support...

All the ISS support spacecraft need launch services. Crew and Cargo Dragon fly on Falcon 9 and Starliner flies on Atlas V, assuming Starliner is going to keep flying. Cygnus has historically flown on Northrup Grumman's Antares rocket but is currently flown on Falcon 9 until a new version of Antares is ready.

Dream chaser is scheduled to fly their winged spaceplane on its first cargo mission to the ISS on a Vulcan Centaur in May of 2025.

This is a largely static market with long-term contracts and with the ISS scheduled to be deorbited in 2030 and an unclear future of NASA space stations, I expect it to be static, with the exception of Boeing having to make a Starliner decision.

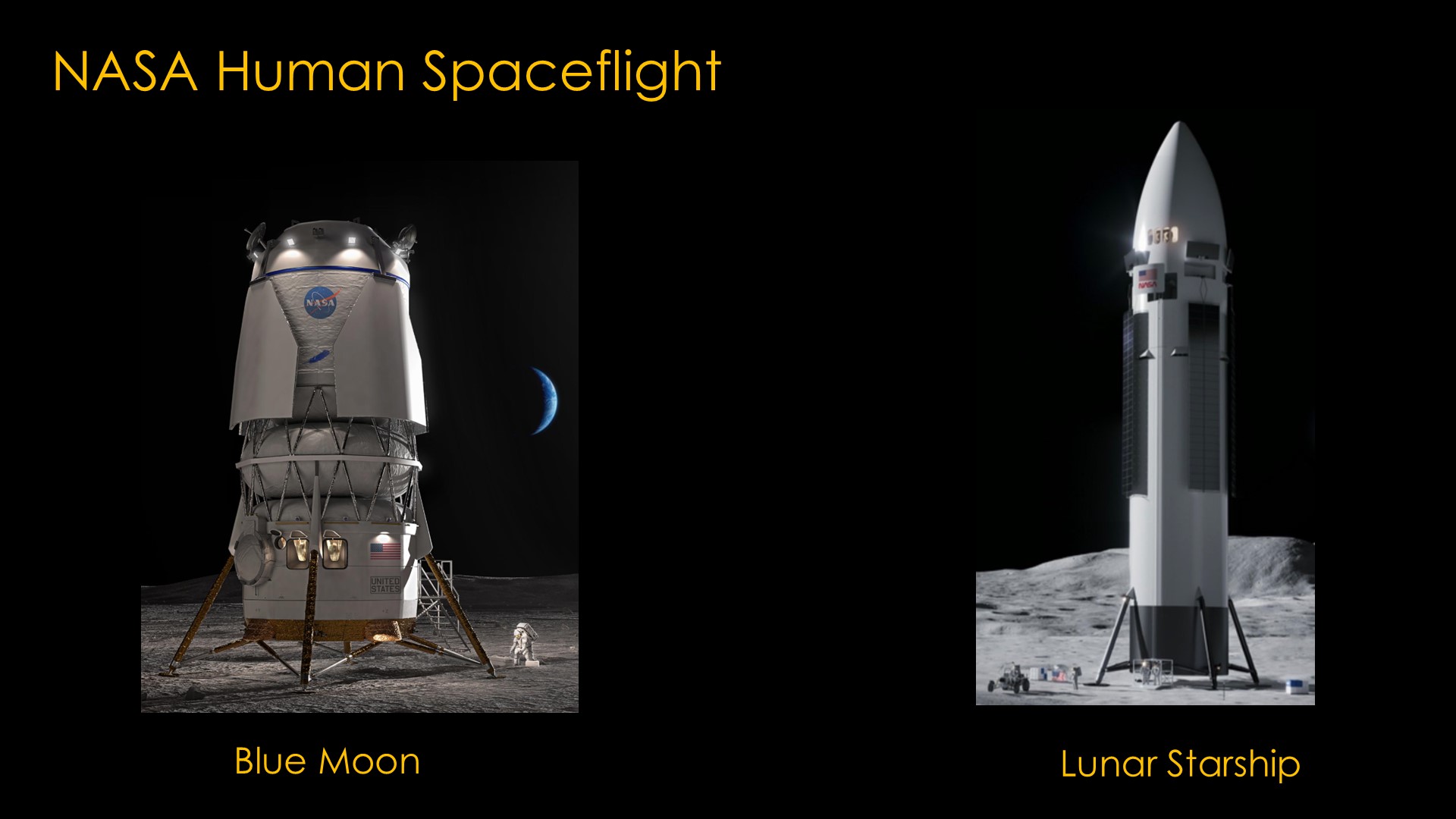

There are of course the two lunar landers - the lunar starship from SpaceX and Blue Moon from Blue Origin. Both are in a bit of a limbo state without an understanding of what the future of Artemis is.

All the human systems are in flux right now.

Those are the launch markets, at least the ones that I wanted to talk about. This view is very US-centric, and ignores launchers in Japan, India, Europe, and China.

The next video will focus on the individual rockets.

If you liked this video about launch markets, maybe you would like to explore some lunch markets.